The safety landscape of 2025 exposed how interconnected modern risks have become. Organizations faced a convergence of cyber threats, traditional workplace hazards, mental health strain, fragile supply chains, and escalating climate risks. Victory Bernard writes that what stood out was not the emergence of entirely new dangers, but how existing risks intensified when systems, people, and leadership were unprepared to respond cohesively.

The five defining safety challenges of 2025 were:

Cyber security Threats: Once considered an IT concern, cyber attacks in 2025 disrupted operations, supply chains, and emergency response systems, demonstrating that digital risks are also safety risks. Cyber incidents increasingly disrupted physical operations, turning digital failures into operational shutdowns.

Traditional Hazards Persist: Falls, unsafe machinery, and inadequate protective measures remained leading causes of workplace injury, compounded by labour shortages and production pressure.

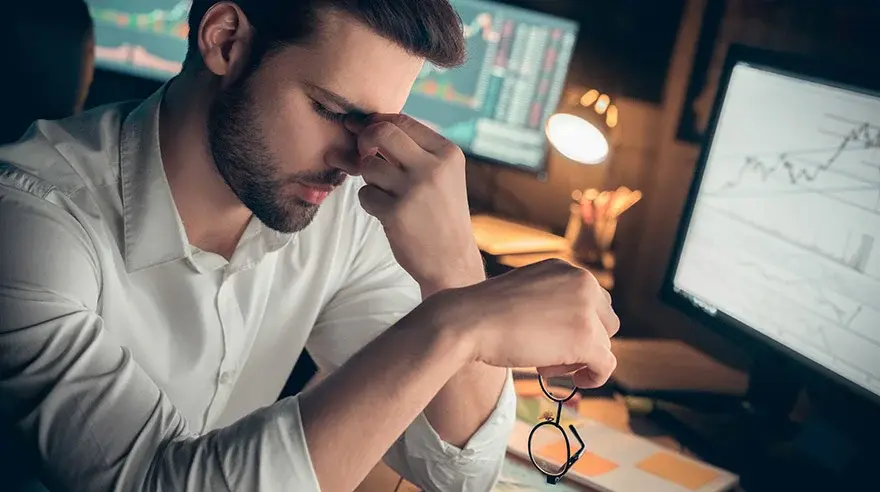

Mental Health Strain: Mental health challenges, once considered peripheral, became central safety concerns as fatigue, stress and burnout affected attention and judgment. These affected attention and decision-making, making mental wellbeing a critical element of workplace safety.

Supply Chain Fragility: Geopolitical tensions, logistics bottlenecks, and reliance on unvetted suppliers created hidden risks that often led to rushed or unsafe practices. Supply chain instability forced difficult operational choices, while extreme weather events placed workers directly in harm’s way.

Climate and Environmental Hazards: Extreme weather events, heat stress, and flooding increasingly affected worker safety and infrastructure resilience.

Expertise Perspective

In an interview conducted by HSENations, Mary Stine, MSc, ASP, Director at ISB Global Corporation, explained that many of the year’s most serious safety incidents escalated because organisations struggled to maintain clarity when multiple risks emerged at once.

She noted that safety leadership begins with a clear and unwavering primary objective. When organisations allow competing pressures- cost, speed, asset protection, or reputation- to blur that objective, teams become uncertain about what to act on first.

According to Stine, this uncertainty often delays action at the very moment decisive response is required.She emphasized that in complex or overlapping events, structured prioritisation is critical. Risks must be addressed deliberately, one at a time, based on their potential impact on human life.

Risk matrices, she explained, provide teams with a shared decision-making framework, enabling faster and more consistent responses under pressure. When such tools are absent or poorly understood, organisations tend to react emotionally rather than strategically.

According to her, “Many incidents occur because teams try to manage everything at once. Focusing on the primary objective allows organisations to act decisively. When life is prioritised consistently, responders make faster and more confident decisions- even in complex situations.”

“Overlapping hazards should be addressed one at a time. Risk matrices and tolerance thresholds provide a shared framework for consistent decisions.” She said.

Stine also highlighted that preservation of human life must always override concerns for property, production, or insured assets. She explained that organisations which clearly embed this principle into training and emergency planning experience fewer severe outcomes because responders are not distracted by secondary considerations.

From a complementary perspective, Mathew Goncalves, Head of Research at Health and Safety Dialogue Company Ltd, observed that 2025 further confirmed the limits of rule-based safety systems. He explained that many organisations continue to treat human error as a failure of discipline, rather than a signal of deeper system weaknesses.

Goncalves stressed that error is normal in complex environments and that blaming individuals after incidents creates fear rather than learning. When workers feel unsafe to report mistakes, near misses, or concerns, organisations lose critical insight into how work is actually done. Over time, this erodes trust and allows risk to accumulate unnoticed.

He further explained that understanding the context in which decisions are made: time pressure, resource constraints, unclear information is essential to improving safety outcomes. According to Goncalves, how leaders respond to bad news determines whether people will speak up the next time something feels unsafe.

He added a human-systems perspective saying: “Error is normal. Incidents do not happen because workers fail—they happen because systems fail to anticipate normal human performance.”

He warned that blame-driven cultures suppress reporting and prevent learning: “When workers fear punishment, near misses are hidden and risks grow unseen. Trust is the most critical safety control.”

Goncalves concluded: “Real learning comes from understanding both incidents and normal work. Workers are experts in how work really gets done, and listening to them prevents harm before it occurs.”

Across industries, 2025 made one reality unmistakable- safety failures rarely stem from a single cause. They occur when weak systems, unclear priorities, and human limitations intersect.