In many African homes and workplaces, the plastic water bottle has become a daily companion—used for storing drinking water, juice, and even hot beverages. But what if that same bottle is silently harming your health?

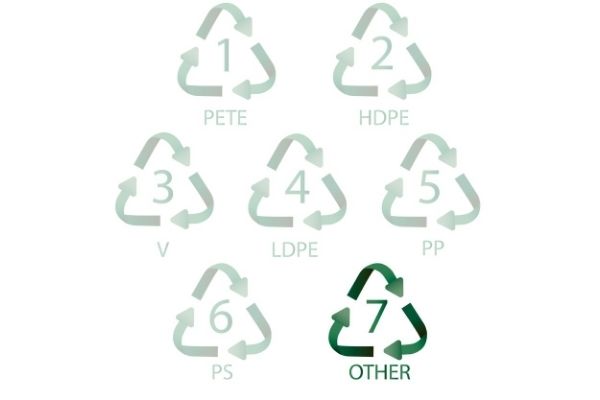

Experts warn that reusing certain plastic bottles—particularly those labelled as #7 or polycarbonate—could be exposing millions of people to toxic microplastics and harmful chemicals like Bisphenol A (BPA), especially when the bottles are washed with hot water or exposed to heat.

The Hidden Risk in Your Water Bottle

Plastics labelled as #7 (often found at the bottom of the bottle inside the recycling triangle) are a blend of multiple types of plastic and are not considered food-safe for repeated use. Studies show that BPA and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals leach from these bottles into the water, especially when heated—such as during washing or being left in the sun.

According to a 2023 report by the African Centre for Environmental Health, up to 47% of households in urban Nigeria and Ghana reuse commercial plastic water bottles, often for weeks or even months without replacement. The report further states that over 30% of respondents admitted to filling hot water into these bottles, unaware of the potential health risks.

What Are Microplastics and BPA?

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles released from deteriorating plastics. When ingested, they can accumulate in the body, potentially leading to inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and even cancer.

BPA is a synthetic compound used in plastic manufacturing. It mimics estrogen in the body and has been linked to reproductive issues, metabolic disorders, and neurological damage. The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that even low levels of BPA exposure can be harmful over time.

African Context: A Widespread Practice With High Risks

In East Africa, a study published in the Journal of Environmental Toxicology found that 85% of roadside water vendors in Nairobi used reused plastic bottles, many of which were visibly degraded. In South Africa, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) identified polycarbonate plastic containers as a major source of domestic BPA exposure.

In Nigeria, where access to safe drinking water and packaging alternatives remains a challenge, the practice of refilling “pure water” and commercial branded bottles is widespread, but poorly regulated.

The Safe Switch

To reduce your risk:

- Stop reusing #7 plastic bottles. These are not designed for long-term use and degrade quickly.

- Switch to glass or stainless-steel bottles, which are durable, heat-resistant, and free of harmful chemicals.

- Choose bottles with wide mouths, making them easier to clean and less likely to retain bacteria or toxins.

- Avoid exposing bottles to heat, whether it’s through washing with hot water or leaving them in a hot car.

While plastics may seem convenient and cost-effective, the long-term health implications—especially in developing African nations—are not worth the risk. Safe hydration starts with safe storage. It’s time to ditch toxic plastic bottles for good.

ALSO READ: The Phone Screen Germs You Can’t See — And Why Hand Sanitizer Isn’t Enough